FOOD ENLIGHTENMENT

Curated Writing About The World of Food

Primer: Introduction To Cookware

This article will survey the various types of pots and pans available, discuss the shapes, sizes, materials, and construction of each, and elucidate how the interaction of those variables can help you choose the right product for a given task. The cooking process involves interaction among the heating source, the cooking vessel, and the food, and the cook, and we'll explain how those issues bear on the choice of a cookware product.

The Old and the New

Pots and pans is one of the few consumer product categories that come to mind in which, even as technology advances, some of the older products are as good as, or better than, the newer products, and continue to improve with age. Take iron. Cooks learned about the advantages the stronger metal iron had over bronze about 2500 years ago. A couple of millennia later, iron was combined with other elements to form steel, a metal that was more durable and less reactive with food than prior substances. The cookware virtues of aluminum, including excellent heat conductivity, were discovered in the 19th century, followed by the process of anodizing to further improve aluminum. Progress continued with the introduction of stainless steel, which incorporated chromium and nickel, and soon manufacturers were bonding layers of different metals to combine the best cooking characteristics of each material. Today, one can find 7-ply cookware, which contains layers of copper, aluminum, and stainless steel in one pot. Yet, with all that progress, when we reach for a pan to cook our burgers and salmon, many of us still use our trusty eight-pound, 12" cast-iron skillet, which, if not inherited from our grandmother, looks and acts just like the one she used years ago.

- Back to Top -

Heat Transfer Basics

Food is cooked by transferring heat from a heat source to the food in one or, more commonly, a combination of ways:

- Conduction, in which heat is transferred via direct contact between the heat source and the cooking vessel/surface, and direct contact between the cooking vessel/surface and the food. An example is routine cooking on a stove.

- Convection, in which heat is transferred to a gas or liquid, usually air, water, or oil, which in turn makes contact with the food. Steam is sometimes part of this process.

- Radiation, in which heat is transferred to the food by electromagnetic waves. Burning coals and live flame in a grill emit thermal radiation.

It's easy to imagine how these modes of heat transfer work in combination: Whenever the outside surface of food is heated by convection or radiation, heat is also transferred toward the interior by conduction. For example, a stove burner heats the pot atop it, and the pot heats both the food (with which it is in direct contact), and the air contained within the pot, especially if the pot is covered to trap the air, which transfers heat to the exterior surface of the food. This typical cooking process illustrates the processes of conduction and convection working simultaneously. In an oven, heat is radiated to the food, the cooking vessel, and the air within the (covered) cooking vessel, an example of a routine cooking process that involves all three of the heat transfer modes. [Note: Microwave cooking is a form of radiation cooking using high-frequency electromagnetic waves, but we don't explore microwave cooking/cookware in this article.]

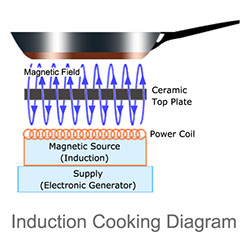

In a newer cooking process, induction cooking, the cooktop heats the vessel placed upon it not by transferring heat from a heat source to the pot, but by inducing an electrical current in the pot. This current is caused by a magnetic field that is generated by wire coils below the surface of the cooktop. As the electric current passes through the electrically resistive metal of the pot, the pot heats up. Stainless steel, with its iron and nickel components, is the main base material used in cookware for induction cooking. Plys of aluminum, valued for their heat-transfer properties, may be contained in the cookware, but they are heated not by the stove, but by the layers of stainless steel to which they're bonded, and by the process of conduction.

In a newer cooking process, induction cooking, the cooktop heats the vessel placed upon it not by transferring heat from a heat source to the pot, but by inducing an electrical current in the pot. This current is caused by a magnetic field that is generated by wire coils below the surface of the cooktop. As the electric current passes through the electrically resistive metal of the pot, the pot heats up. Stainless steel, with its iron and nickel components, is the main base material used in cookware for induction cooking. Plys of aluminum, valued for their heat-transfer properties, may be contained in the cookware, but they are heated not by the stove, but by the layers of stainless steel to which they're bonded, and by the process of conduction.

- Back to Top -

Control and Performance

On a stovetop, where conduction is the primary mode of heat transfer, control over the cooking process means managing the heat source and choosing the cooking vessel that appropriately transfers the heat to the particular food. The degree and rate of heat transfer can be controlled by the user who has learned how specific pots react on the stove burner, i.e., how quickly they heat up and cool down. Certain cooking characteristics change with the shape of the pans: Liquid from cooking food will evaporate more quickly in a pan with flared sides than in one with straight sides, for example. The evenness with which the pans transfer heat over the cooking surface and up the sides of the pot is determined by the materials, design, and quality of the pot. Some pans, desirably, heat unevenly, like carbon steel woks, in which high-temperature cooking is done in the center of the pan, and lower-temperature cooking is done on the cooler, sloped edges, allowing for control of individual ingredients. Choosing the right size pot or pan for the task at hand is as important as choosing the right vessel. The proportion of cooking-area to side-area affects the rate of evaporation during the cooking, with higher ratios providing faster evaporation. Independent of cooking area, the more angled the sides of the pan are, the faster the evaporation rate during cooking. It's important to choose a pan size that doesn't force you to bunch the food food together or leave a lot of cooking surface open. Overcrowded food in a pan inhibits the evaporation from the cooking food; instead of escaping into the air, moisture exuded from the food is absorbed by adjacent food, making for soggy results. A pan that is too large creates new empty spots on the cooking surface, especially when the food is being moved around, making it harder for the pan to maintain a constant temperature, which can result in uneven cooking.

- Back to Top -

Performance Characteristics

The characteristics of the cookware materials that affect performance are:

Heat transfer properties – how quickly and evenly the material heats up and cools down when the heat source is applied and removed, and when unheated food is added to the pan. For this article we've devised a 1-10 scale to express this conductive property. Roughly speaking, there's an inverse relationship between heat conductivity and heat retention, and some cookware materials and/or construction methods are limited in the quantity of heat they can handle.

Reactive properties – Most of the metals used to make pots and pans will leach (in small amounts) into some foods during cooking. Common implications of this chemical interaction between cooking surface and ingredients range from:

- Acceptable, as when beneficial trace amounts of iron, or chromium from stainless steel, are introduced into the food.

- Not-so-good, as in the discoloration of acidic foods such as spinach turning black when its oxalic acid reacts with iron.

- Bad, as when metals impart a metallic flavor to the food, again occurring most commonly with acidic foods like citrus, tomatoes, and wine.

- Potentially toxic, as when a poorly made or damaged aluminum or non-stick pan sheds chemicals that can be a health hazard.

Other surface characteristics, such as the level of stickiness/release, indicate the degree to which the cooking surfaces hold the food. This can be a factor in the quality of the browning and searing produced by the pan that contributes, through caramelization, to the flavor of the food. If the surface has a high degree of release, cooked food will be easier to remove, and the pan will be easier to clean. All cooking surfaces have some texture. Depending on the surface material and the foods cooked, some bonding will occur during cooking. Poached eggs are particularly sticky because of the bonding properties of the protein molecules in the egg and the liquid that allows the food to seep into the texture of the cooking surface.

Durability is the degree to which cookware surfaces are susceptible to scratching, chipping, burning, and wearing thin. In extreme cases, pots made of more than one metal can separate from their base. The bodies of pots, especially inexpensive metal pans, can warp. Some softer metals, such as aluminum, are dent-prone; harder metals, like cast iron, can crack.

- Back to Top -

Design and Construction

Before examining in-depth the materials used to make pots and pans, it is useful to gain a basic understanding of the configurations in which those materials are rendered into cooking vessels. The construction configuration can maximize the beneficial qualities of a given material. The design of other pot components, like handles and covers, play a meaningful role in ease of use. Many of the characteristics highlighted here are discussed in further detail below.

Single material – Iron, aluminum, various kinds of steel, and other materials are cast (molten metal is poured into molds), or stamped pressed, spun, or rolled by a machine.

Anodized or other enhanced material – Metals can be put through various processes to improve their material characteristics. When anodizing metal, usually aluminum, the metal is oxidized chemically and/or electronically, producing a smooth, more durable coating. Annealing is another oxidizing process, achieved by a heating and cooling cycle that strengthens the steel and makes it more resistant to corrosion.

Lined material – Classic cookware configurations include copper pots lined with a cooking surface of tin, nickel, stainless steel, or silver. This combines the excellent heat transfer properties of copper with the non-reactive characteristics of the other metals.

Enameled material – A metal, usually cast iron or steel, is covered with a porcelain- or glass-based coating, which is smooth and non-reactive

Clad – Two or more layers of different metals are bonded together to reap a combination of benefits: A bonded copper bottom and aluminum core (producing excellent heat transfer) with a stainless steel cooking surface (for strength, versatility, and ease of release) is a premium 3-ply configuration. A more common and affordable 3-ply setup is stainless-aluminum-stainless. Also available are 5- and 7-ply configurations. Since the 1960s, when John Ulam, the founder of All-Clad, first developed a roll-bonding process of sandwiching layers of different metals together, clad construction has become the dominant format for high quality pots and pans.

Disk bottom – While the entire body of the pot (bottom and sides, up to the rim) in clad cookware are constructed of the bonded layers of different metals, a disk bottom configuration combines materials only in the bottom (base) of the vessel. The base is usually a 3-ply disc, with a core of aluminum sandwiched between two layers of stainless steel, bonded to the body of the pot. This is a great format for saucepans and stockpots used mainly for boiling and sautéing; however, for other tasks the lack of heat conduction in the sides can lead to uneven results.

Handle design – Some 12" cast iron skillets weigh 11 pounds. An 8-quart Dutch oven can tip the scales at 20 pounds before you fill it up. Ample, well-designed handles can make the difference between a pot that is easy to use, clean, and store, and one that is difficult, if not dangerous, to use. Handles are under-appreciated at time-of-purchase; great handles make using a piece of cookware a pleasure. Depending on design, the handles on cast pots can get very hot. Most cookware has handles, often made of a different material than the body, riveted, bolted, or welded to the body. Some pots have wooden handles, prone to burning in a hot oven. Dutch ovens sometimes come with bucket handles, and many large pots come with a pair of loop or tab handles (tab handles are similar to loop handles, but don't have the open space within the handle).

Covers – Sauce pans, dutch ovens, and stockpots are routinely sold with covers, as are some skillets. Some covers are metal, others are glass, rimmed by a metal. Covers are essential to properly perform those tasks in which convection cooking plays a major role.

Cooking surface color – Usually slightly gray, the colors of cooking surfaces range from the black of cast iron to the white of porcelain-based enamel. The performance implication of color is that the darker the shade, the more heat-absorbent the surface. In practical terms, lighter shades make it easier to see the food as it cooks.

- Back to Top -

Prices and Warranties

Cookware purchasers cite product quality twice as frequently as price as the most meaningful factor in their purchasing decisions, according to the Cookware Manufacturer's Association, a trade organization. In the Pots and Pans pans category the adage "you-get-what-you-pay-for" is meaningful, but less so than it is in other kitchen equipment categories, like small appliances, where lower prices often mean plastic, not metal parts, or smaller, weaker motors that affect the performance and shorten the lifespan of the product. In cookware, because of the widely divergent costs of different materials, expensive pots aren't necessarily better. One of the most common cooking vessels found in American kitchens is a 12" cast iron skillet. The manufacturer Lodge has been making cast iron cookware for more than a century, and sells its bestselling 12" pan for $25. Viking, renowned American range maker since the early 1980s, sells a 13" non-stick skillet for $324. Both companies, like most pan manufacturers, offer a lifetime warranty against defective products and, while non-stick formulations continue to improve, the $25 Lodge, if properly used, will likely outlast the expensive Viking pan by several decades. To get the most from your cookware dollar, take advantage of the less expensive material options, like the cast iron mentioned above, or a large, affordable aluminum or enameled steel pot for boiling items such as lobster, pasta, and corn instead of spending several times as much for a stainless-clad steel stockpot. Many cookware makers guarantee their products for a lifetime -- the buyer's, not the product's. Some, particularly manufacturers of porcelain- and glass-based pans, carry one- or two-year warranties. Other companies specify thirty or fifty years. With the exception of non-stick, which should be replaced when the finish begins to wear down (usually within ten years), well-made, properly cared-for cookware of every variety should last long enough for you to pass them on to the next generation.

- Back to Top -

Materials

For this article we have devised a 1-10 scale to denote the thermal conductivity of a given material, relative to other materials used to make cookware. The numbers represent the amount of heat transmitted through a unit thickness in a measure of time. We don’t assign conductivity numbers to coatings such as non-stick, enamel, or for processed metal, which has an outer coating on a base metal.

Copper

Rating 10 Among all metals commonly used in the manufacture of cookware today, copper, especially when configured in thick layers, provides the fastest transfer rate, and the most even distribution, of heat. Only silver, of the metals used to make cookware, is more responsive to heat than copper. The Belgian company Deymeyere is one of the few manufacturers that still use silver in some of its pans. Silver is the proverbial 11 on a scale of 1 to 10 -- thank you Nigel Tufnel. (To nitpick, though, silver is 10.75) Copper is highly reactive, especially with acidic foods. Traces of the mineral that leach into food can impart a metallic taste or verdigris-green color to the food. Overused, copper cooking surfaces are potentially toxic. Because of its reactivity, most copper-pot cooking surfaces are lined with tin or stainless steel, and less commonly with nickel or silver. None of these will react with acidic foods, though silver will tarnish and leach with sulfurous ingredients like kale, onions, garlic, egg yolks, and some meat and fish. All but stainless will scratch and wear off over time, at which point a good pot can be relined for about half the cost of a new pot, if you can find a good metal smith to do the work. But most of the copper used in today’s cookware is as either an internal core, or as an exterior (bottom and sides) layer. In addition to cookware, copper is used in high-end mixing bowls, in which a particularly beneficial reactivity is prized by many bakers: Copper ions bond with one of the proteins in egg whites, strengthening the walls of the air bubbles produced when the whites are whipped. The result is a more stable foam with firmer peaks. Copper is more expensive than other cookware material, often costing twice as much as stainless steel and four times as much as cast iron. The classically good-looking metal tarnishes quickly but is fairly durable: with proper care (hand-washing, hand-drying and regular polishing) copper pots, pans and bowls will last for 40+ years.

- Back to Top -

Aluminum

Rating 6.6 for rolled, pressed or spun aluminum; cast aluminum is slightly less conductive. The most abundant metal on the planet, aluminum is, ounce for ounce and dollar for dollar, the most useful of the cookware metals, especially as a heat transferring core material. About 55% of the cookware sold in the U.S. is aluminum, compared to 36% for stainless steel. It's commonly used in bakeware, and is ubiquitous in foil wraps. In addition to its excellent heat transfer properties, aluminum is relatively inexpensive, lightweight, strong, and does not require excessive maintenance. Aluminum's drawback is that it reacts with acidic and alkaline foods, which can affect the taste of the food, and raises health concerns. High concentrations of aluminum in the body can be hazardous, though the portion of the metal ingested by your body from cookware is small compared to what you get from drinking water, eating processed foods, taking some medicines, and using cosmetics. Aluminum was first introduced as a cookware material in 1892 by the Pittsburgh company that later became ALCOA (ALuminum COmpany of America). During most of the 1900s, pots and pans of pressed, rolled, stamped, and cast aluminum were extremely popular for their affordability and ease of use. Seasoned properly, a cast aluminum pan can be a good substitute for a heavier, less responsive cast iron pot. You can sauté and flambé more quickly using an aluminum pan than you could using cast iron. Aluminum use in cookware has changed dramatically in the past 40 years as a result of two developments: metal-cladding and anodizing, both of which offer improvements over the former common aluminum cookware construction configurations. In both clad and disk-bottomed pots/pans, aluminum is used as a core for its high thermal conductivity, and bonded to one or more layers of stainless steel, which usually comprise the cooking surface. Anodized aluminum has the versatility, performance, durability, and low-maintenance of the non-anodized metal, along with two major benefits: The surface is approximately 30% harder than stainless steel, and anodizing counters the reactive properties of aluminum without significantly impairing the heat-transfer characteristics. It provides a much smoother, stick-resistant cooking surface which, in high-quality pots, performs more evenly than exposed aluminum. It shares the same 1,221-degree F melting point of aluminum, but is more impervious to wear. It can be used to make a variety of pot types, and is economical.

- Back to Top -

Cast Iron

Rating 1.5

Cast iron pans were mass-produced at foundries in the US decades before electrified factories helped coin the phrase mass–production. What it lacks in quick thermal responsiveness, cast iron makes up for with thermal density and stability. Well-made pans heat slowly and evenly, can be heated to very high temperatures, and retain the heat well. Cast iron is used most often in skillets, griddles, grill pans, and Dutch ovens. One important consideration is that most pans are made from a single pour of molten iron into a mold, so the handles heat up along with the rest of the pan. Cast iron is heavy and fairly high-maintenance compared to stainless or aluminum, for it needs to be regularly seasoned with fat or oil to protect against rusting and reacting to food, and to counter the clingy–ness of the porous surface of the metal. Many manufacturers season their pans at the factory, which saves the user some work with new pans. Cast iron is inexpensive and extremely durable as long as you don't abuse it or subject it to thermal shock (by pouring cold water into a hot pan). Cast iron pans should be cleaned with hot water and salt, not soap, and immediately dried by hand or with heat on a stove burner. The performance of a properly cared-for, well-made cast iron pan will improve over the course of its long life.

- Back to Top -

Stainless Steel

Rating .5

Yes point five, very non-conductive. In 1915, after nearly a century of experimenting with the alloying of metals, two Americans applied for a patent for the iron/chromium/nickel combination which we know today as stainless steel. There are many variations of the alloy, most of which include other components in addition to the three mentioned above, and in which the ratios of the elements differ. 18/10 stainless, for example, contains 18% chromium and 10% nickel. Within a few years cookware makers recognized it's durability and non-reactive properties and began turning out stainless pots and utensils. Because of its strength, resistance to rust and corrosion, affordability, and low-maintenance characteristics, manufacturers have devised methods of optimally combining stainless with better heat conductors, mitigating the poor conduction properties of the alloy. Today about 30% of all cookware sold in the US contains stainless as a base and handle material, and/or a cooking surface, for its low reactivity with acid and alkaline foods. The light silver color of the stainless surface makes visual monitoring of the cooking process easy, as compared to pans of iron or anodized aluminum, with their darker surfaces.

- Back to Top -

Carbon Steel, Blue Steel, Black Steel

Rating 1.4

During the second half of the 19th Century the Industrial Revolution was given a serious shot in the arm when methods to mass produce steel were developed. Carbon (an element) and minerals were added to iron, producing a family of stronger, lighter metals that were easy to work with in the manufacturing process. These metals began to be used in industries as diverse as railroads, building construction, and consumer products. Blue and black steel are so called because of the colored layer of oxidation that results from an annealing process (heating and slowly cooling the metal) that further strengthens the steel and makes it more corrosion-resistant. Even though steel heats slowly, carbon steel has high-heat capacity and has been a prized cookware material for searing, braising and stir-frying for generations, best known these days in Chinese woks. The steel needs to be seasoned regularly to keep the pan from rusting and sticking to food. As with cast iron, use a water/salt combination to clean the pans, and immediately thoroughly hand dry.

- Back to Top -

Aluminized Steel

Rating N/A While this material is more frequently found in bakeware, it does appear in stove top pots. To create aluminized steel, steel is dipped in a bath of a molten aluminum-silicon alloy, creating a thin layer next to the steel core, and an outer layer of aluminum oxide. Steel treated this way is not quite as durable as stainless, but it’s significantly more corrosion resistant than regular steel, and will conduct heat more quickly and evenly.

- Back to Top -

Nonstick

Rating N/A

Nonstick (often spelled as non-stick) is a non-reactive category that includes a wide variety of combinations, largely comprised of synthetic materials used mostly for cooking surfaces, sometimes for pan exteriors. The original nonstick surface was inadvertently discovered in 1938 by a chemist working for DuPont. He was experimenting with refrigerant gases when he produced a waxy solid–polytetraflouroethylene, or PTFE, which had extremely slippery surface characteristics. DuPont patented the formula, and trademarked the chemical, calling it Teflon, in 1945. Ten years later a French company, Tefal, bonded PTFE to aluminum and introduced the first non-stick cookware. In 1960 the US Food and Drug Administration approved PTFE, and T-fal, as the company was known in the States, began marketing Teflon pots and pans in North America. Nonstick surfaces are chemically inert; because of their atomic structure, they don't bond readily with food with which they come into contact. A low-friction molecule of PTFE is comprised of carbon and fluorine, the result of which is a material that has high cohesive force, but little adhesive force. PTFE molecules are much more prone to bond with like molecules than others, a tendency that results in their the nonstick property. Before the introduction of Teflon in consumer goods, and continually over the 55 years since, debate has proceeded about possible health hazards of the cooking surface material. In particular, PTFE, can break down when heated to more than 550°F, and release fumes that can cause flu-like symptoms in people. In 2005, perfluorooctanoic acid, or PFOA, a key processing agent in the formulation of nonstick surfaces, was labeled a likely carcinogen by the Environmental Protection Agency. At this time, we are not aware of any manifestations of toxicity in users of Teflon or other nonstick cookware, but you should perform due diligence if you have questions or reservations about using products with this material. When using nonstick cookware, don't overheat the pans. Don't leave empty pans on a high burner for long periods of time, don't use them in the broiler or over a live fire. Use only plastic or wooden utensils on the cooking surface, and plastic scrubbers or sponges, not steel wool, to clean those surfaces. When the surface begins to degrade, dispose of the pan. Nonstick surfaces wear out much more quickly than any of the materials we've discussed so far, with the exception of tin, which is no longer commonly used. The toxicity questions, as well as environmental concerns, helped fuel progress made by manufacturers in improving nonstick surfaces over the past forty years. Many formulas eliminate PFOA, and many of them substitute other materials for PTFE. Various ceramic components, glass-reinforced nylon, silicone, silicon oxides, and other polymers have been employed as makers patent new cookware formulations and manufacturing processes. Thermolon, ScanPan, Ecolon, Xylan are a few brand names of these new breeds, all successors of Teflon. A major functional difference, and sometimes a drawback, of nonstick cooking surfaces is that when food sticks less it browns less, producing fewer fond–caramelized bits of cooked food that add flavor to a dish or sauce or gravy. Nonstick cookware runs the price gamut. Our neighborhood dollar store sells a non-stick skillet three-pack (8", 10", and 12") for $8. Viking, best known for its stoves, has a line of nonstick skillets that sell for about $250 a pan. As with all cookware, quality and lifespan depend on the manufacturing specifications and process, including thickness of the base, the number of layers in the coating, and the method by which the coating is applied. Unlike well-made cast iron or clad pots and pans, even top-quality nonstick models generally are not equipment you'll be passing on to future generations.

- Back to Top -

Enamel

Rating N/A

Adding enamel to provide a non-reactive, low-maintenance cookware surface predates by thirty years the advent of the non-stick surfaces described above. Compared to the application of the much thinner nonstick layer(s), the process of enameling cookware is simpler, and requires fewer chemicals. A porcelain glaze, usually a type of glass with a high boric oxide component that makes it resistant to high temperatures and to corrosion, is fused onto pots. This coating approach is used for cast iron pots of various shapes, and for plain, untreated steel. The latter category, for its light weight and affordability, is common in cookware for camping and for large stockpots and roasting pans. Enameled cast iron is best known in Dutch ovens, a category dominated by the colorful, and often pricey, Le Creuset lines. Even on the pots with brightly covered exteriors, the cooking surface is usually white to provide optimal visibility of the food as it cooks. Enamel cooking surfaces enhance the functional capabilities of the pots to which the coatings are applied. For example, you'd use an enameled Dutch oven for the same tasks for which you'd use a seasoned but uncoated cast iron Dutch oven. An enameled pot is suitable for cooking acidic foods, like tomatoes, for which you'd avoid reactive, uncoated iron. Enamel coatings are more fragile than the material to which they're fused. Enamel is prone to chipping or cracking when struck sharply and overheated. Because of the chemicals used in the kiln firing process, it's best not to use an enameled pot in that doesn't have a completely intact cooking surface.

- Back to Top -

Titanium

Rating .5

This light, lustrous, strong metal is a new addition to cookware material choices. It is used as a component in non-stick formulas as well as a body material. As a cooking surface (usually a component in a ceramic formulation), its non-stick qualities are superior to most other formulations. Appliance makers are starting to use titanium pots in their counter top units, such as in some of the new electric rice cookers.

Ceramic

Rating ~ 1.5

Made primarily from clay, this material is usually processed using high-temperatures and glazing to produce a glass-like surface. Ceramic cookware, including porcelain, stoneware and earthenware, is commonly used in an oven, not on a stove top. Ceramic vessels are more insulating than conductive, so they heat up slowly. For dishes like lasagna and casseroles, this is an advantage over metal cookware, the surfaces of which are prone to overcook in a highly conductive roasting pan. Well-made ceramic pots distribute heat uniformly and retain heat longer than metal pots. We discuss ceramic materials in kitchenware in detail in a separate article.

Glass

Rating 1.05

Functionally, glass cookware is very similar to ceramic cookware. It's less expensive and at least as durable as most kiln-fired cookware. It has a higher tolerance for thermal changes, is impervious to some of the vulnerabilities of glazed pieces, such staining and absorbing odors. Glass cookware can chip easily, though a small chip may not render the product unusable.

- Back to Top -

Pot and Pan Types

Skillet

The skillet, or frying pan, is probably the most-used and most functional type of pan in a cook's arsenal. We fry, sauté, and sear in it, and cook meat, fish, vegetables, eggs, and pancakes in it. It has a flat bottom, flared sides of between 1"- 2.5" inches, and a long handle. The pans range in size from 6"–14", and run the gamut of cookware metals and configurations. Chef's pans and stir-fry pans may have slightly higher sides to facilitate more vigorous mixing of ingredients, while omelet pans might be shallower and more accessible to spatulas to enable easy turning and flipping. Several manufacturers offer oval versions of the shallow skillets, calling them fajita pans.

Circulon non-stick skillet Lodge 12 inch cast-iron skillet

- Back to Top -

Sauté pan

Similar to the skillet, this pan takes its name from the French verb sauter, to jump, as the food is often tossed inside the pan. Sauté pans are often used for frying and searing, in addition to sautéing. Sauté pans, available in a variety of materials and construction configurations, have straighter and higher (up to 4") sides than a skillet, making them less spatula-accessible. The straighter sides provide a larger cooking surface than a fry pan with the same base dimensions. These differences, and the fact that sauté pans usually come with a lid, make them more appropriate for making sauces and other liquid creations where a higher degree of containment and control over evaporation is required. For kitchen tasks in which the pan is transferred from stove top to the oven, a sauté pan is more likely to be used than a skillet. Some manufacturers specify the size of their sauté pans by liquid capacity, others by exterior diameter.

Similar to the skillet, this pan takes its name from the French verb sauter, to jump, as the food is often tossed inside the pan. Sauté pans are often used for frying and searing, in addition to sautéing. Sauté pans, available in a variety of materials and construction configurations, have straighter and higher (up to 4") sides than a skillet, making them less spatula-accessible. The straighter sides provide a larger cooking surface than a fry pan with the same base dimensions. These differences, and the fact that sauté pans usually come with a lid, make them more appropriate for making sauces and other liquid creations where a higher degree of containment and control over evaporation is required. For kitchen tasks in which the pan is transferred from stove top to the oven, a sauté pan is more likely to be used than a skillet. Some manufacturers specify the size of their sauté pans by liquid capacity, others by exterior diameter.

- Back to Top -

Saucepan

Saucepans signify a decisive step in the direction of liquid cooking with their high, straight sides and tight-fitting lids. A saucepan's capacity is usually designated in quarts, instead of exterior dimensions. Available in all of the cookware materials and in sizes from 1 to 5 quarts, saucepans are the go-to pots for soups, vegetables, grains, cereals, and many sauces. The Windsor pan has flared sides that facilitate evaporation for sauce reductions, and provide greater stirring access to the corners of the pot. (Pictured: Farberware 3-quart saucepan)

Saucepans signify a decisive step in the direction of liquid cooking with their high, straight sides and tight-fitting lids. A saucepan's capacity is usually designated in quarts, instead of exterior dimensions. Available in all of the cookware materials and in sizes from 1 to 5 quarts, saucepans are the go-to pots for soups, vegetables, grains, cereals, and many sauces. The Windsor pan has flared sides that facilitate evaporation for sauce reductions, and provide greater stirring access to the corners of the pot. (Pictured: Farberware 3-quart saucepan)

- Back to Top -

Saucier

This variation of a saucepan is distinguished by its shorter, and slightly contoured sides. The curved sides better accommodate whisks and spoons for stirring or otherwise moving food around as it cooks. A Windsor pan is another saucepan variation, usually 2.5 quarts or smaller, with a narrow bottom and angled sides. The Windsor was designed specifically for reducing sauces.

All-Clad Cop-R-Chef 2 quart saucier and Wolfgang Puck Bistro Elite 2 quart Windsor pan

- Back to Top -

Stockpot

Deeper than it is wide, with two loop handles instead of the single straight (or slightly curved) handle of the pots we've described so far, the stockpot is designed to cook and simmer large amounts of food, from stock, soups, and stews to pasta and lobsters. Usually with a heavy bottom and substantial cover, these pots are designed more to protect against burning during a long, slow cooking process than they are are for responsive heat reaction. Depending on the amount of food you cook for a typical meal, the stockpot, which comes in capacities from 6-20 quarts, may not be a pot you use every week. But for a clam bake, or a Superbowl chili for a large group, the stockpot is essential. Common stockpot capacities range from 10-14 quarts. (Pictured: 12-quart Anodized Calphalon stockpot)

Deeper than it is wide, with two loop handles instead of the single straight (or slightly curved) handle of the pots we've described so far, the stockpot is designed to cook and simmer large amounts of food, from stock, soups, and stews to pasta and lobsters. Usually with a heavy bottom and substantial cover, these pots are designed more to protect against burning during a long, slow cooking process than they are are for responsive heat reaction. Depending on the amount of food you cook for a typical meal, the stockpot, which comes in capacities from 6-20 quarts, may not be a pot you use every week. But for a clam bake, or a Superbowl chili for a large group, the stockpot is essential. Common stockpot capacities range from 10-14 quarts. (Pictured: 12-quart Anodized Calphalon stockpot)

- Back to Top -

Dutch oven

The oldest cooking vessel still widely used in the Western world, the Dutch oven originated in Holland in the 17th century, and was cast using sand molds. The Dutch oven was originally used over an open flame, suspended by a bucket-type handle, and is still the favored pot at campfires. Most of the models used today, on the stove top and in the oven, are of heavy cast metal, fitted with domed lids and two loop handles. Also called casseroles, the enameled models, with non-reactive and low-maintenance surfaces, have become more popular in past thirty years than the uncoated cast iron models. They come in a variety of bright colors, with prices ranging from $50-$400. Dutch ovens are used predominantly for slow cooking stews, soups and sauces, braising, pot-roasting, and boiling. At least one manufacturer, Le Creuset, calls some of their pots French ovens. (Pictured: Le Creuset 7.25 quart Dutch oven)

The oldest cooking vessel still widely used in the Western world, the Dutch oven originated in Holland in the 17th century, and was cast using sand molds. The Dutch oven was originally used over an open flame, suspended by a bucket-type handle, and is still the favored pot at campfires. Most of the models used today, on the stove top and in the oven, are of heavy cast metal, fitted with domed lids and two loop handles. Also called casseroles, the enameled models, with non-reactive and low-maintenance surfaces, have become more popular in past thirty years than the uncoated cast iron models. They come in a variety of bright colors, with prices ranging from $50-$400. Dutch ovens are used predominantly for slow cooking stews, soups and sauces, braising, pot-roasting, and boiling. At least one manufacturer, Le Creuset, calls some of their pots French ovens. (Pictured: Le Creuset 7.25 quart Dutch oven)

- Back to Top -

Wok

The most common cooking vessel in east Asia, the wok became popular in the West during the 1970s. This bowl-shaped pan, typically 14" diameter and 4" deep, is usually used to stir-fry, which involves cooking food quickly over high heat. It can also be used to braise, deep fry, steam (using baskets), smoke, and even sauté, but it is most impressive when in the service of a cook who can use the directly heated bottom of the pan and the cooler, sloping sides as two different cooking surfaces, cooking several different ingredients within one pan. The wok is traditionally is round-bottomed, to be used over a flamed heat source, but there are flat-bottomed versions as well, for use on contemporary gas, electric, and ceramic stove tops. A typical wok may have a pair of metal or wood loop handles, but many woks have long stick handles to facilitate tossing the food as it cooks, using a tugging motion on the pan. Carbon steel is the most common material used to make woks today, with cast iron a popular second choice. Construction methods, price, and quality vary widely in woks available today.

Carbon Steel wok

- Back to Top -

Double boiler

The double boiler is comprised of a sauce pan nested halfway down into a slightly larger sauce pan. The larger pan, on the bottom, holds water that transfers heat from the stove to the top pot, which contains the food. Usually, the water is brought to a boil, and the steam, contained by the tight fit between the two pots, does the work. The point of the double boiler is to heat the food more gently than is easily accomplished using direct heat. The double boiler is the right choice for tasks such as clarifying butter, melting chocolate, and working with delicate sauces that tend to separate. (Pictured: Calphalon 5 quart stainless steel double boiler)

The double boiler is comprised of a sauce pan nested halfway down into a slightly larger sauce pan. The larger pan, on the bottom, holds water that transfers heat from the stove to the top pot, which contains the food. Usually, the water is brought to a boil, and the steam, contained by the tight fit between the two pots, does the work. The point of the double boiler is to heat the food more gently than is easily accomplished using direct heat. The double boiler is the right choice for tasks such as clarifying butter, melting chocolate, and working with delicate sauces that tend to separate. (Pictured: Calphalon 5 quart stainless steel double boiler)

- Back to Top -

Pressure cooker

Introduced by Presto in 1939, the pressure cooker is similar to a stockpot. Pressure cookers are usually made of stainless steel, often with a cladded disk bottom, are available in sizes from 6+ quarts, and come with a sealable lid. The pressure that results when the lid is locked down allows the temperature of the boiling water/steam to reach about 250° F, so that food is cooked in a fraction of the time the same task would take in an open pot. [In a standard, uncovered pot, boiling water/steam reaches a maximum of 212° F before it evaporates.] The faster process results in a higher retention of flavor and nutrients, while saving time and energy. Internal pressure is regulated by a weighted or spring-loaded valve. Pressure cookers, both stovetop and electric countertop models, are used for a wide variety of cooking tasks, from searing to sautéing, preparing soups and stews, as well as cuts of meat and fish and vegetables. (Pictured: Manttra 6 quart stainless steel pressure cooker)

Introduced by Presto in 1939, the pressure cooker is similar to a stockpot. Pressure cookers are usually made of stainless steel, often with a cladded disk bottom, are available in sizes from 6+ quarts, and come with a sealable lid. The pressure that results when the lid is locked down allows the temperature of the boiling water/steam to reach about 250° F, so that food is cooked in a fraction of the time the same task would take in an open pot. [In a standard, uncovered pot, boiling water/steam reaches a maximum of 212° F before it evaporates.] The faster process results in a higher retention of flavor and nutrients, while saving time and energy. Internal pressure is regulated by a weighted or spring-loaded valve. Pressure cookers, both stovetop and electric countertop models, are used for a wide variety of cooking tasks, from searing to sautéing, preparing soups and stews, as well as cuts of meat and fish and vegetables. (Pictured: Manttra 6 quart stainless steel pressure cooker)

- Back to Top -

Griddle

A griddle is a flat pan with a low perimeter lip, as opposed to actual sides, which retains fat in the pan, while providing unfettered spatula access. Griddles come in a variety of sizes and shapes. Most are heavy, of cast iron or aluminum, and meant to be used on a stove top, sometimes across two burners. They are ideal for pancakes, eggs, bacon, and hamburgers -- almost anything you'd cook in a skillet -- and want to turn with a minimal effort. The particular advantage offered by stove top griddles over skillets or fry pans is more, easily accessible cooking surface area.

KitchenAid 11" non-stick griddle

- Back to Top -

Grill pan

A grill pan is similar to a griddle, but with evenly spaced ridges built in to the cooling surface, designed to cook food much the way it would cook on a grill over live fire. Effectively, the grill marks on the food are the prominent characteristic common to food cooked in a grill pan and food cooked over a fire. Grill pans are available in a slew of shapes and sizes, and come in all of the materials commonly used in cookware. Heavier pans are favored for the high-temperature cooking usually undertaken with grill pans. Stick-resistant and non-stick cooking surfaces make cleaning cooked-on greasy foods from the channels between the ridges manageable; however, as noted above in our nonstick section, be careful not to exceed manufacturer's specifications regarding heating the pan to a certain temperature.

Le Creuset 12" oblong grill pan and Staub 12" American grill pan

- Back to Top -

Roasting pan

Sometimes called a baking pan, roaster, lasagna pan, or gratin, most models are fairly heavy rectangular pans of stainless steel, or clad or anodized aluminum. Some baking pans have non-stick finishes. There are many porcelain-finished and enameled casserole-dish-type roasting pans in various shapes which have some common utility with the metal versions; the metal pans are often favored because they can more dependably be used on the stovetop, for searing and browning. The most popular roasting pan sizes are between 14"–16", they have 3"–4" sides, usually easily accommodate a wire rack, and are used most frequently to oven-roast turkeys, large cuts of meat, big batches of vegetables. Sturdy, vertical handles are important for moving the pan in and out of the oven, particularly when you have a 15–pound bird in it. And some pans come with covers, some with racks. (Pictured: Calphalon 16" x 13" roasting pan with rack)

Sometimes called a baking pan, roaster, lasagna pan, or gratin, most models are fairly heavy rectangular pans of stainless steel, or clad or anodized aluminum. Some baking pans have non-stick finishes. There are many porcelain-finished and enameled casserole-dish-type roasting pans in various shapes which have some common utility with the metal versions; the metal pans are often favored because they can more dependably be used on the stovetop, for searing and browning. The most popular roasting pan sizes are between 14"–16", they have 3"–4" sides, usually easily accommodate a wire rack, and are used most frequently to oven-roast turkeys, large cuts of meat, big batches of vegetables. Sturdy, vertical handles are important for moving the pan in and out of the oven, particularly when you have a 15–pound bird in it. And some pans come with covers, some with racks. (Pictured: Calphalon 16" x 13" roasting pan with rack)

- Back to Top -

Roasting rack

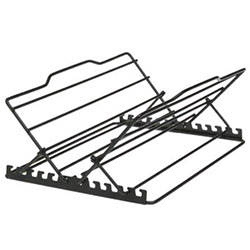

For cradling roasting meat above the pan, allowing for even heat distribution over the entire surface, and for drippings to accumulate in the pan below, roasting racks are concave or V-shaped, sometimes adjustable, sometimes not. The better-designed racks have handles to enable lifting the food from the pan. The frames are metal, and many racks come with a non-stick finish. (Pictured: NorPro adjustable roasting rack)

For cradling roasting meat above the pan, allowing for even heat distribution over the entire surface, and for drippings to accumulate in the pan below, roasting racks are concave or V-shaped, sometimes adjustable, sometimes not. The better-designed racks have handles to enable lifting the food from the pan. The frames are metal, and many racks come with a non-stick finish. (Pictured: NorPro adjustable roasting rack)

- Back to Top -

Broiler pan

Nordic broiler pan

Broiler pans are usually rectangular, and available in a variety of sizes. They're often shallower than a roasting pan, and are routinely configured in two parts: a 1"–2" high bottom drip pan, into which fits a flat, slotted pan onto which the food is set. Broiler pans are used for broiling in an oven with the heat source above the food. They're frequently of enameled steel, usually of a lighter–gauge metal than roasting pans, and usually aren't suitable to go on a stove burner. (Pictured: Nordic broiler pan)

Broiler pans are usually rectangular, and available in a variety of sizes. They're often shallower than a roasting pan, and are routinely configured in two parts: a 1"–2" high bottom drip pan, into which fits a flat, slotted pan onto which the food is set. Broiler pans are used for broiling in an oven with the heat source above the food. They're frequently of enameled steel, usually of a lighter–gauge metal than roasting pans, and usually aren't suitable to go on a stove burner. (Pictured: Nordic broiler pan)

- Back to Top -

Brasier pan

A braisier pan is like a stockpot with inverse proportions: it'ss shorter than it is wide, and comes with a tightly fitting cover and loop handles. Most commonly, meat is braised by initially searing it to brown its surface (and seal in moisture), then cooking it slowly to tenderize the meat. The second part of this process resembles the common tasks for which Dutch ovens are used, and, similarly, there are cast iron and ceramic brasier pans, though stainless steel and heavy–gauge aluminum are more prevalent in these pans. Capacities range from about 6–18+ quarts. (Pictured: All-Clad 13 inch braiser pan)

A braisier pan is like a stockpot with inverse proportions: it'ss shorter than it is wide, and comes with a tightly fitting cover and loop handles. Most commonly, meat is braised by initially searing it to brown its surface (and seal in moisture), then cooking it slowly to tenderize the meat. The second part of this process resembles the common tasks for which Dutch ovens are used, and, similarly, there are cast iron and ceramic brasier pans, though stainless steel and heavy–gauge aluminum are more prevalent in these pans. Capacities range from about 6–18+ quarts. (Pictured: All-Clad 13 inch braiser pan)

- Back to Top -

Pasta pot

These pots warrant mentioning for the functional advantage they offer when cooking large quantities of boiled food. Pasta pots offer two variations on the stockpot, and are available from several manufacturers. One version has a basket insert with holes in it, like a colander, that holds the food and can be removed, leaving the cooking water behind. The other variation has a locking lid with a built-in, adjustable vent/strainer, which acts as a built-in colander. In this version, the pot is overturned into the sink, draining the water and leaving the cooked food in the pot. (Pictured: Lagostina pasta pot)

These pots warrant mentioning for the functional advantage they offer when cooking large quantities of boiled food. Pasta pots offer two variations on the stockpot, and are available from several manufacturers. One version has a basket insert with holes in it, like a colander, that holds the food and can be removed, leaving the cooking water behind. The other variation has a locking lid with a built-in, adjustable vent/strainer, which acts as a built-in colander. In this version, the pot is overturned into the sink, draining the water and leaving the cooked food in the pot. (Pictured: Lagostina pasta pot)

- Back to Top -

Paella pan

The traditional pan used to make this multi-ingredient, saffron rice-based Spanish dish is a shallow, large diameter pan of carbon steel, and resembles a flattened wok. The paella pan usually has a 16"+ flat, cooking surface with narrow, flared sides and two loop handles. Like the wok, the paella pan has been modernized, and models include products of enameled steel, aluminum, clad stainless, and some with non-stick finishes. Paella pans are distinguished from similarly shaped flat pans, such as skillets, by their (paella pans) larger cooking surface.

Paderno carbon steel paella pan

- Back to Top -

Crepe pan

A crepe pan is a variation on the skillet, and is designed to cook and facilitate the release of thin, delicate crepes. Available in several sizes, 10" is common. Crepe pans feature lower, more-flared sides than most skillets to enable spatula and turner access for flipping the crepes. Blue steel and non-stick are the materials most frequently used in crepe pans. (Pictured:DeBuyer 10 inch non-stick crepe pan)

A crepe pan is a variation on the skillet, and is designed to cook and facilitate the release of thin, delicate crepes. Available in several sizes, 10" is common. Crepe pans feature lower, more-flared sides than most skillets to enable spatula and turner access for flipping the crepes. Blue steel and non-stick are the materials most frequently used in crepe pans. (Pictured:DeBuyer 10 inch non-stick crepe pan)

- Back to Top -

Butter warmer

Originally designed to melt butter on the stovetop, this is effectively a miniature sauce pan, with a capacity of typically between 12–16 ounces, and handy for warming small amounts of liquids. Butter warmers also work well for making simple syrup and other heated ingredients, boiling a couple of eggs, and sanitizing contact lens cases. (Pictured: Ruffoni butter melter)

Originally designed to melt butter on the stovetop, this is effectively a miniature sauce pan, with a capacity of typically between 12–16 ounces, and handy for warming small amounts of liquids. Butter warmers also work well for making simple syrup and other heated ingredients, boiling a couple of eggs, and sanitizing contact lens cases. (Pictured: Ruffoni butter melter)

- Back to Top -

Asparagus cooker

Asparagus cookers are designed to hold asparagus vertically so that the bottom ends of the vegetable are submerged in a few inches of water and boiled, while the tips are steamed more slowly at the top. This configuration results in a tall cylindrical pot, usually stainless steel, with a diameter of around 6", and typically with a 3 quart capacity. Usually, a steel basket insert is included, which is used to hold the asparagus spears upright. (Pictured:Swift 14 cm stainless steel asparagus cooker)

Asparagus cookers are designed to hold asparagus vertically so that the bottom ends of the vegetable are submerged in a few inches of water and boiled, while the tips are steamed more slowly at the top. This configuration results in a tall cylindrical pot, usually stainless steel, with a diameter of around 6", and typically with a 3 quart capacity. Usually, a steel basket insert is included, which is used to hold the asparagus spears upright. (Pictured:Swift 14 cm stainless steel asparagus cooker)

- Back to Top -

Tagine

Tagines originated in North Africa as shallow earthenware pots used for low-temperature, slow-cooking of stews and other dishes. Several European manufacturers have modernized this pot, making its use more functional in a modern kitchen. Using current ceramic technology, these two-piece pots – a round base with a tall, conical cover – are stovetop–ready. Pronounced tah-'zheen.

Traditional Moroccan tagine

- Back to Top -

Fondue set

Fondue is a Swiss dish in which pieces of food are dipped into a warmed sauce or oil. Most of think of contemporary fondue as melted cheese, into which we can dip small pieces of meat, bread, fruits, and vegetables. The fondue is heated in a communal pot, usually placed over a small, portable heat source of alcohol or other fuel. Electric fondue sets are commonplace now, adding a general-safety factor to the product. Because fondue sets are often stylish, there are many variations; however, the basic set consists of a burner of some type, a container placed above the burner to hold the fondue, and 4–8 fondue forks/spears to hold the food for dipping. Electric sets often have an electric base, a stainless steel container, an earthenware double-boiler, and utensils.

Swissmar fondue set; Schokoladen tealight fondue set; Avalon electric fondue set

Swissmar fondue set; Schokoladen tealight fondue set; Avalon electric fondue set

- Back to Top -

Universal lids

A number of manufacturers sell separate lids with concentric ridges to fit coverless pots and pans. With the ring diameters in the 8"–12" range, finding a match for which the fit between pan and cover is perfect is hit-or-miss, but for often-used pans in need of a lid, this can be an inexpensive solution. Most top manufacturers offer replacement lids for their products, but don't manufacture universal lids. (Pictured: Nordic Ware universal lid: 8–12 inches)

A number of manufacturers sell separate lids with concentric ridges to fit coverless pots and pans. With the ring diameters in the 8"–12" range, finding a match for which the fit between pan and cover is perfect is hit-or-miss, but for often-used pans in need of a lid, this can be an inexpensive solution. Most top manufacturers offer replacement lids for their products, but don't manufacture universal lids. (Pictured: Nordic Ware universal lid: 8–12 inches)

- Back to Top -

Grill press

Grill presses are used to improve contact between the food and the cooking surface. Applying two or more pounds of downward pressure to cuts of meat, fish steaks and fillets, vegetables, or to grilled sandwiches, ensures more even exposure to the heat, speeding up the cooking process, and bringing out desirable cooked surface characteristics. Presses are usually made of cast iron, with stay-cool wood or steel handles, and come in a variety of sizes, shapes and weights. (Pictured: Kingsford circular grill press)

Grill presses are used to improve contact between the food and the cooking surface. Applying two or more pounds of downward pressure to cuts of meat, fish steaks and fillets, vegetables, or to grilled sandwiches, ensures more even exposure to the heat, speeding up the cooking process, and bringing out desirable cooked surface characteristics. Presses are usually made of cast iron, with stay-cool wood or steel handles, and come in a variety of sizes, shapes and weights. (Pictured: Kingsford circular grill press)

- Back to Top -

Splatter screens

Frying in an uncovered pan results in airborne hot oil and grease more often than not. Saucepan cooking, even simmering, usually results in some liquid splatter. To prevent dangerous hot liquid from jumping from the pan, and to keep the stovetop less messy, manufacturers devised splatter screens. These round wire mesh screens, typically 8"–12"+ in diameter, with straight handles, are set across the top of a pot or pan to solve the splatter problem, a better solution than donning a red shirt every time you make tomato sauce. Splatter screens are often sold in 3-piece sets of 8", 10", and 12" screens. (Pictured: Norpro 13 inch splatter screen)

Frying in an uncovered pan results in airborne hot oil and grease more often than not. Saucepan cooking, even simmering, usually results in some liquid splatter. To prevent dangerous hot liquid from jumping from the pan, and to keep the stovetop less messy, manufacturers devised splatter screens. These round wire mesh screens, typically 8"–12"+ in diameter, with straight handles, are set across the top of a pot or pan to solve the splatter problem, a better solution than donning a red shirt every time you make tomato sauce. Splatter screens are often sold in 3-piece sets of 8", 10", and 12" screens. (Pictured: Norpro 13 inch splatter screen)

- Back to Top -

Cookware Sets

Cookware sets are available in many construction and material configurations, and range from well under $100 to All-Clad's $2000 14-piece, 7-ply set with copper cores. The sets at the bottom of the price spectrum – under $40 – tend to have uneven heat transfer properties and don't wear well. As a rule, all the pieces in sets are of the same material, most commonly stainless steel or anodized aluminum, which makes for a matching set of cookware, but limits you to one material. Most cooks, if asked to list their ideal cookware of six pots/pans, would include three main materials, or two base materials and three cooking surface materials. An example of six pieces (not including lids, though manufacturers DO include lids when they refer to the number of pieces in a set) that would well-equip a kitchen:

- 12" skillet, cast iron

- 10–12" skillet, nonstick

- 2 quart saucepan, clad stainless steel

- 4 quart saucepan, clad stainless steel

- 7 quart Dutch oven, enameled cast iron

- 12 quart stockpot, clad stainless steel

Some experts feel that the downside to purchasing a cookware set is that you'll pay for and store pots and pans you'll never use. It's unlikely you'd "never" use a piece of cookware from a set, and it also pays to keep in mind that experts' advice is generally meant to promote culinary excellence, and can miss the point for many aspiring cooks. The most important thing to do if you want to learn to cook well is to practice. Cookware sets offer a lower entry price-point. Instead of making six separate decisions about which pots and pans to purchase you can make one, buy a decent set, and get cooking. Whether you buy stainless, or anodized, or other nonstick format, by the time you're ready to expand your repertoire with specialized pots, you'll have gotten the hang of at least one kind of cooking surface. It's easier to branch out from there. Finally, keep in mind that it's not unusual for most cooks to supplement their cookware with additional pieces over time.

- Back to Top -

Care & Storage

To ensure longevity, pots and pans must be properly stored and maintained. Correctly storing cookware prevents it from being damaged as it's removed for use and put it away after use. The preferred storage method is to hang pots and pans from a rack, and to place porcelain and glass pans on a shelf. When pieces must be stacked on top of on another, place a paper towel or clean kitchen towel between them to keep them from scraping against each other. To maintain cast iron and untreated steel, perform regular seasoning by applying oil to the pan surface, heating the pan in a 350-degree oven for an hour or so, letting the pan completely cool, then gently wiping away residual oil before storing. This video (YouTube) demonstrates the process. Many cast iron and steel pots come pre-seasoned from the factory. Clean those metals with water and salt (don't use soap, which can strip away the seasoning), and dry them immediately and thoroughly to stave off rust.

Innova wrought iron hanging pot rack

- Back to Top -

FOOD ENLIGHTENMENT

Copyright © 2019–2022 FoodEnlightenment.com. All Rights Reserved. PLEASE SEE OUR PRIVACY POLICY.